Baku - COP29: What Really Happened?

- Andrea Ronchi

- Nov 24, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Nov 25, 2024

Why This is the First COP Since Paris Where Real Progress Was Made, Despite Many Crying Failure.

On Saturday night, COP29 in Baku concluded, where I had the opportunity to participate as a “party overflow,” allowing me to observe the formal negotiations firsthand.

The essence of COP29 is that with the approval of Article 6—the legitimization of CO2 markets—the principle of “a ton-is-a-ton” from the Kyoto Protocol was reinstated. This principle means that it doesn’t matter who or where a ton of CO2 is reduced or removed; what matters is doing it quickly and efficiently. This breakthrough paves the way to overcoming the biggest obstacle in climate negotiations: the divide between countries that pay and those that receive funding.

To everyone asking how it went, I respond with two key takeaways that, surprisingly, are rarely reported by mainstream journalists.

The Divide Between Paying and Recipient Countries Is (and Remains) the Core Issue

One of the pillars of the Paris Agreement is the distinction between developed countries, tasked with financing the transition, and developing countries, which are the beneficiaries of these funds. However, this classification is becoming increasingly problematic as nations like China, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE are still considered developing countries.

In the Blue Zone (the restricted area of COP), walking through the pavilions felt like attending a BRICS event. The pavilions of China, India, Brazil, and Gulf countries were bustling for the full two weeks with high-ranking officials and packed schedules of side events. In contrast, the US pavilion resembled a lemonade stand. China also hosted numerous events in African pavilions, showcasing its ongoing colonization efforts disguised as decarbonization contributions, financing strategic infrastructure in exchange for exclusive access to mineral reserves.

Looking at the negotiations from this angle, the potential for the next Trump administration to withdraw from the Paris Agreement again doesn’t seem so far-fetched. It’s hard to justify the US footing the bill for China’s transition when Beijing continues to invest its resources in initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative, reinforcing its monopoly on resources vital for global decarbonization.

Developing countries and Western progressive groups decry the agreement reached on Saturday night, which commits developed countries to provide $300 billion annually until 2035 for mitigation, adaptation, and resilience projects in developing countries. The target was over $1 trillion annually. Developing countries (including China) may voluntarily contribute to this $300 billion fund, but their recipient status will remain unchanged. Meanwhile, the US, Europe, and Japan will always have to open their wallets without ever being eligible as recipients.

CO2 Markets Are Back at the Center of Climate Negotiations, Along With Hope for Breaking the COP Deadlock

On the first day, there was widespread excitement when the COP29 President, Mukhtar Babayev, Azerbaijan’s Minister of Ecology and Natural Resources, announced that approving Article 6 was the key goal of COP29. He stated, “By efficiently aligning buyers and sellers, carbon markets can reduce the cost of achieving climate targets by over $250 billion annually. In a world where every dollar counts, this measure is ESSENTIAL.”

The key aspects of Article 6 lie in Articles 6.2 and 6.4:

Article 6.2 enables countries to trade “internationally transferred mitigation outcomes” (ITMOs). These CO2 credits represent emission reductions that can be traded between countries to meet their national targets (NDCs). Initial rules for transparency, trade registration, and avoidance of double-counting have been established to ensure the system’s integrity.

Article 6.4 introduces a UN-managed international carbon credit mechanism, the Paris Agreement Credit Mechanism (PACM). This allows countries and private actors (companies, institutions, etc.) to generate and trade certified CO2 credits from projects that reduce or remove greenhouse gas emissions in an additional, permanent, and verifiable manner.

It felt like reinventing the wheel since the UN had already created the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) after Kyoto for the same purpose. The methods may differ now, but the essence remains. What’s changed is that the world, now facing tougher challenges, has returned to support the only tool capable of achieving decarbonization goals: the market.

This will also reshape how companies use offsets, allowing them to pursue their targets with greater confidence. Voluntary protocols like SBTi and national regulations will inevitably have to adapt.

European Greens and left wings Cry Failure

Before COP29, European Greens and progressive factions strongly opposed the use of international carbon credits. Swedish MEP Isabella Lövin emphasized the need to avoid double-counting and ensure absolute transparency in reduction projects. German MEP Michael Bloss called international markets “greenwashing,” arguing that European companies should focus solely on domestic reductions.

However, this perspective ignores the reality of a globally interconnected economy where every ton of CO2 saved has the same climatic impact, regardless of origin. Denying efficient economic tools risks slowing and increasing the cost of the transition.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

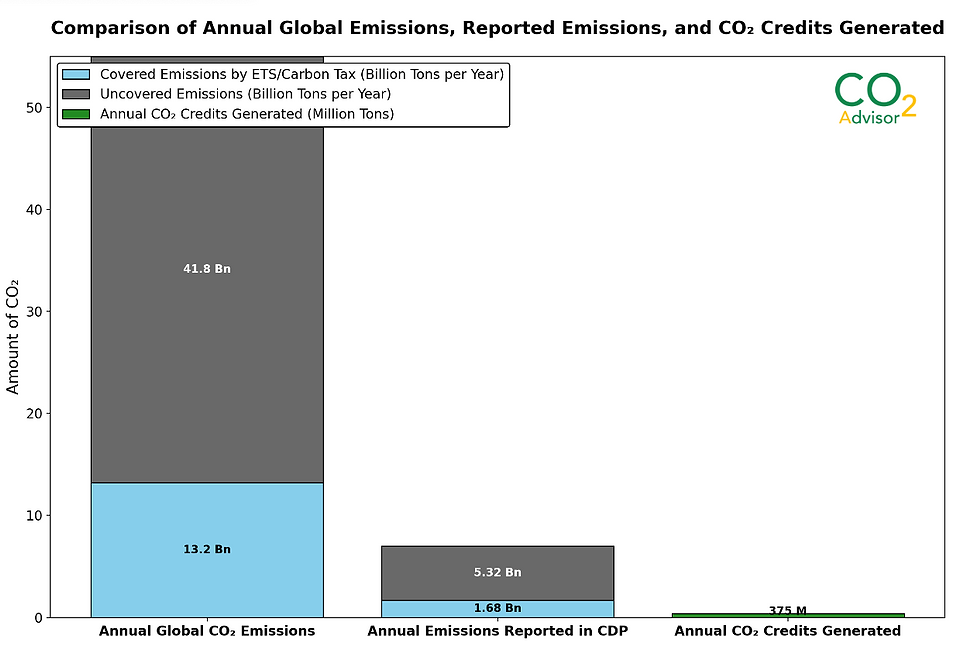

Globally, only 372 million CO2 credits currently meet standards recognized by IETA-ICROA (International Emissions Trading Association - International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance). Even if some of these aren’t flawless, global emissions total 55 billion tons of CO2, 41 billion of which are not covered by mandatory carbon pricing systems (like emission trading or carbon taxes).

372 million vs. 41 billion.

While no one will explicitly admit that offsets are an alternative to direct reductions (to avoid upsetting radical audiences), the market will make offsets prohibitively expensive. Today, the average price of CO2 credits is around $7 (World Bank). Most analysts predict prices exceeding $150–200 by 2030. This will spur a race for public and private decarbonization projects, rewarding the lowest marginal cost solutions for CO2 abatement.

Conclusions

COP29 in Baku marks a pivotal moment in climate negotiations. The approval of Article 6 is not just a technical step forward but a political one, bringing back an indispensable economic tool for decarbonization.

Despite criticisms, it’s essential to recognize that a well-regulated market system offers the only viable path to a fair, swift, and economically sustainable transition. The challenge now lies in translating these agreements into tangible actions.

Comments